Below is the story of how we discovered my grandfather’s secret life and true identity. It’s what kick-started my love of genealogy and desire to learn more about my roots and help others find theirs. I’ll warn you now: it’s a long one. I didn’t want to cut corners, although there are still so many more fascinating details that could have been included. If you have similar stories or questions or even information about my grandfather, please share them in the Comments section at the end, or contact me privately. Permission to share this story publicly has been graciously granted by all those involved.

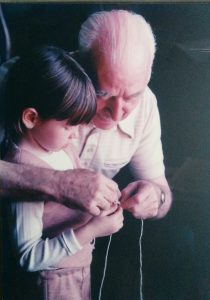

My Grampi was a storyteller at heart. Every time I saw him, he would animatedly share an adventure from his past, usually with a few fist slaps and a satisfied laugh. He was a larger-than-life character to his two young granddaughters, often greeting us by pinching our cheeks hard ‘til we were squealing in pain. “Hallo, honeychild”, he’d roar, followed by a bone-crushing hug. We always looked forward to his jokes and playing cards and listening to him reminisce about his life.

Our grandfather told many stories about living in poverty as a child with abusive and alcoholic parents. In 1923, at the age of fourteen, he ran away from home to join a British Navy training ship, leading to service around the world until 1932. The stories he shared on paper and in person about his life in the Navy and later in the Army during WWII were vivid, detailed and full of pride. He bragged of his physical stamina, the fights he got into (which of course, according to him, he always won), the adventures he found around the globe, and the fact that he never drank alcohol because he didn’t want to repeat the mistakes his parents had made.

Grampi was also a romantic at heart and unapologetic about his love for his wife, my grandmother, Molly. We often heard the story of how they met at the bus stop at the Bramley Depot, where they were both stationed at the beginning of the war. He left behind love letters and war journals full of heartfelt notes to “Skipps”.

But although he was a prolific storyteller, Grampi was mysteriously selective about the information he shared about his life before 1939. If asked about a detail outside of the accounts he’d already told, he’d shut down the question quickly and decisively.

Following Grampi’s death in 1997, my father felt it was time to learn more about his past, so he requested Grampi’s military records from England and provided the Ministry of Defence (MoD) Records Office with the names and dates of the ships on which he’d served. But to our great surprise, they responded that no Palmer had served on those ships at those times. There was absolutely no doubt in our minds that Grampi had been on those ships, so my father persisted and asked the MoD to check the crew lists for the three ships we knew of, with the service dates we had to see if anyone matched our details. Incredibly, they did this, and found one person who matched Grampi’s service history. But his name wasn’t Reuben or Alfred or Frank Palmer, the names we had known him by. It was Alfred Page. The date of birth and physical description, down to the tattoo of “two hearts with a sprig of flowers on the right forearm”, and a scar over the right eye, matched Grampi.

That wasn’t all; the MoD provided one other shocking detail: Alfred Page had enlisted in the Territorial Army in Liverpool in 1937 and in September 1939, just a few weeks after WWII began, he deserted the unit. Desertion? In a time of war? This didn’t match up at all with the proud military man we knew who, as Reuben Alfred Frank Palmer, had endless stories, service records, journals, and photographs of himself serving in the Second World War.

At this point, we knew he’d served in the Navy as a Page and later in the army in WWII as a Palmer. But why the name change? A closer look at the parents listed on Grampi’s Palmer birth certificate, Minnie Price and Reuben Palmer, showed that they only married ten years following his birth. The certificate itself was also issued almost twenty years after his birth. So was it possible that Minnie had given birth to him illegitimately and given him up to be raised by the Pages in Liverpool? We theorized that he discovered the details of his “true” birth as an adult and requested his Palmer birth certificate. By that time, Minnie was married to Reuben Palmer, who perhaps agreed to have his name listed as the father on the certificate. It seemed like a stretch, but it explained the names and birth certificate.

And his desertion from the Territorial Army? When he enlisted in 1937 as Alfred Page, this regiment was viewed somewhat as a “weekend soldier’s” unit and in September 1939 was not expected to leave British soil during what everyone thought would be a short war (later, however, they did end up seeing extensive action). It made sense to us that Grampi, being the fighter that he was, would have done whatever he could in order to get himself overseas. Even if that included deserting the Territorial Army in order to re-enlist with the Royal Army Ordnance Corps (R.A.O.C.) under a new name: Palmer.

Fast forward twenty years, when I found myself researching the Palmers and Pages. I discovered that a Reuben Palmer had been born as per Grampi’s birth certificate, with all of the same details except for the birth year: 1928 instead of 1909. Both Grampi and this second Reuben were listed in the UK Registration Index of Births, but Grampi’s was pencilled in after the fact. This, in combination with the fact that the parents weren’t married until 1919, started to throw suspicion on our Palmer birth certificate.

Soon after, I found a Page grandson who had posted his family tree on Ancestry.com, including family photographs. The physical similarities between Grampi and my own father to the Page family were uncanny. This grandson told us that his uncle Alfred had deserted the army in 1939 and that he last saw him just prior to 1952, when my grandparents emigrated to Canada. He was certain that Alfred Page was a full-blooded Page and he’d always wondered what had happened to him.

By now, our certainty that Grampi was a Palmer was crumbling. Could it really be true that Grampi was Alfred Page and that he had completely fabricated the Palmer name? It was difficult to process: my father had lived his entire life as a Palmer; my sister and I had lived our entire lives as Palmers; I’d even given the name Palmer to both of my children as middle names. The Grampi we knew was a devoted family man with strong morals. It seemed inconceivable that he would have lied about his birth or obtained an illegal birth certificate.

Shortly after this revelation, I connected with another Page relative – this time someone claiming to be Alfred’s grandson. This man said that not only had Alfred deserted the Army in 1939, but in doing so, he also abandoned a wife and son. They never heard from him again. Now, as far as we’d always known, my sister and I were his only grandchildren since my father was his only son. The idea that Grampi had had a son before my father came as a complete shock, particularly when we were still trying to adjust to the idea of a fraudulent name.

As impossible as it was to believe, slowly, more and more evidence emerged that eventually proved that my grandfather truly was Alfred Page, born and raised in Liverpool; that he had a son from a previous marriage; that he was never divorced; that he went AWOL in 1939; that he illegally changed his name and went on to fight in WWII; that he married my grandmother, fathered a second son, and moved to Canada in the 1950s.

Grampi’s first son, this uncle I never knew existed, was alive and well at eighty-six years old when we discovered all of this. I eventually got up the nerve to call him, having no idea whether or not he would be resentful or interested in getting to know us. To my great relief, he was warm and welcoming. Seventy-seven years after he last saw him, my uncle was thrilled to learn about what had happened to his father. He was excited to meet his new little brother, my Dad. Although he was just nine years old when his father left, he had no hard feelings towards him. For me, it was like speaking with my grandfather again – he and Grampi shared the same accent, love of adventure, and talent for storytelling.

My feelings after the call were in turmoil and I still found it difficult to reconcile Grampi’s actions with regards to his eldest son. But I was viewing Grampi through my 21st century North American lens and I realized I had very little understanding of his circumstances a hundred years ago. So, in order to get a better grasp of that era, I re-read Grampi’s memoirs, immersed myself in histories of the Liverpool slums of the early 20th century, and researched the origins of our Page ancestors.

Grampi hadn’t descended from the Palmer family of English coal miners as we’d always thought. Instead, three out of four of his grandparents were born in Liverpool to Irish immigrants, most likely fleeing the Potato Famine in the mid-nineteenth century. Irish refugees in Liverpool at this time were often penniless and had no choice but to take on the lowest paying jobs. The population explosion in Liverpool made for crowded, unsanitary dwellings; in 1847 alone, over 300,000 Irish arrived in Liverpool, more than doubling the populationi. They often had no choice but to move into crowded dwellings and dark, damp cellars, and they were predominantly viewed by the English as lazy, poor, filthy, and too fond of their drinks. Surviving from one day to the next was a desperate feat. Men, if they had a bit of spare money, often squandered it in the pubs, while their wives were left with the children, usually unable to feed and clothe them all properly.

Things weren’t very different by the time Grampi was born in the slums in 1909. According to Grampi, his father wasn’t around much and his mother, living in desperate conditions, also drank and beat him badly at times. Grampi’s memoir vividly describes the abuse, sharing a bed with several siblings, not having enough clothing between themselves and a relentless hunger. He felt that the Navy had saved him from this life; it was a chance for him to work hard and earn respect, not to mention a decent paycheque, and he revelled in the adventures it offered. Life was looking up and he looked forward to a life-long career in the Navy. But in 1932, at the onset of the Depression, the Navy was forced to downsize and Grampi, along with thousands of other seamen, were effectively kicked out onto the streets. It was a crushing blow. Suddenly, he was back where he started in Liverpool but now, he was surrounded by thousands of unemployed men and had a wife and child to support. He knew no trade; his only experience was a life on the sea, skills that were of no use in the bustling city of Liverpool.

His wife managed to find work as a housekeeper, but Alfred roamed the country in search of work, sometimes sleeping in the streets or a doss house (the cheapest sort of rooming house), sometimes starving for a couple of days until he could collect his dole of six shillings on Fridays. It wasn’t enough to support himself let alone a wife and child. Grampi wrote in his memoirs:

Charlie [Grampi’s pseudonym] used to draw his dole of six shillings on a Friday morning, then set off to find work, at first he tried to live like a human being, by renting a room, but that cost two and sixpence a week, so he had to give it up in order to make his money stretch in buying food. Then he took to sleeping out to make things stretch, but after three or four days his money would be gone and he would have to starve until he got his dole again on the Friday.

In 1934, Grampi managed to enlist in the 1st Battalion of the Scots Guards and the following year was sent to Egypt. A year after his return, he began working on the buses of Liverpool and enlisted in the Cameron Highlanders Territorial Army. He felt he was “playing soldiers” in this unit, but it was the closest he could come to a military life.

By 1939, Alfred had spent most of the first nine years of his son’s life abroad or out of work. He’d seen very little of his family and most likely spent much of that decade feeling bitter towards the Navy, and perhaps shame for his inability to earn a decent living, support his family or to serve in the military. With the outbreak of WWII, Grampi probably saw an opportunity to redeem himself. As he wrote: “Well, Charlie was not one to let things like a war go on without his being involved, after all he was a fully trained man, with both land and sea experience”. And so, he deserted the Territorial Army and enlisted as Alfred Palmer in the R.A.O.C., where he found the adventures he craved within the challenging conditions of the war. Perhaps he was also trying to escape his difficult marriage.

It’s impossible to know what his long-term plan was, or if he even had one. Like everyone else at that time, he probably thought the war would be over by Christmas. He might’ve planned on returning to Liverpool and his old name, thinking he’d get just a slap on the wrist for going AWOL, as he’d proven his bravery and loyalty to Britain during the war by joining the R.A.O.C.

Whether he planned on going back or not, what he didn’t expect was to meet my grandmother, less than two months after he changed his name and just six weeks before he was to leave for France. “At last he had found somebody that he really loved,” he wrote. They were quickly engaged and planned to marry upon his return from France. He “gave her a bent old penny, telling her that ‘the bad penny always turns up’”, knowing he now had a chance for a different life as a Palmer, with a woman he adored.

Learning about all of this gives some insight into Grampi’s behaviour, but in the end, we’ll never know everything that happened. Perhaps it’s unforgivable that he left his first wife and son; perhaps he felt he had no other choice. Ironically, it was my new uncle himself who helped in the acceptance process, saying early on that “I want you to know that I have no hard feelings about any of this and I’m very happy to know all about it.” He doesn’t know why his parents fell out or who was at fault, but as he says, “it’s all in the past and long done with, so it doesn’t matter now, does it?” So, who am I to judge Grampi when the son he left behind harbours no hard feelings?

In early 2017, my father, with my mother, travelled to England to meet his new-found half-brother and nieces and nephews. It was a long-overdue family reunion full of stories of Grampi and their own lives. My own chance to meet our new family came a few weeks later and it was a whirlwind of emotions. My uncle looks and sounds just like Grampi. He’s a proud man and a storyteller, just like his Dad. I had to constantly remind myself that this was not my grandfather as it felt like I was seeing Grampi again, twenty years after his death. For the little girl who idolized and adored her grandfather, it was an unimaginable gift.

I often wonder what Grampi would think of us uncovering all, or most, of his secrets. He’d be angry, I know, but so long as my grandmother didn’t know the truth, he might be forgiving. I wasn’t about to let go of the mystery, after all, I inherited his stubbornness. His secrets haven’t affected the memories I have of him and my love and respect for him remain unchanged. What’s more, I have gained an incredible uncle, four dear cousins, a passion for family history research, and a strong appreciation of my roots in Liverpool and Ireland.

I often wonder what Grampi would think of us uncovering all, or most, of his secrets. He’d be angry, I know, but so long as my grandmother didn’t know the truth, he might be forgiving. I wasn’t about to let go of the mystery, after all, I inherited his stubbornness. His secrets haven’t affected the memories I have of him and my love and respect for him remain unchanged. What’s more, I have gained an incredible uncle, four dear cousins, a passion for family history research, and a strong appreciation of my roots in Liverpool and Ireland.

i. “Irish Immigration to England,” Irish Genealogy Toolkit (http://irish-genealogy-toolkit.com/Irish-immigration-to-England.html : accessed 17 July 2017).

A riveting story, very well told.

Oh my Marie what a fascinating story , until you read into the life your great, great, great grandparents had to endure and bring all the problems they had over the whole history of the family is remarkable.

I am incredibly envious of all of the tremendous hard work you’ve put in to find what you have. Well done.

Thank you so much, Ron!

many stories like this turn up when researching and doing DNA studies. Absolutely fascinating how people survived and changed what they felt they had to, or just let it go and only a few knew the truth from ‘back then’

In my family too and my husband’s as well, all sorts of new family members to welcome and sort out with love.

Glad you got to know some of your other relatives too!

That’s a great way of putting it: “all sorts of new family members to welcome and sort out with love.” Thank you for sharing!